Persistent vectors, Part 2 -- Immutability and persistence

An implementation of a vector class that is immutable, persistent, and efficient takes some non-trivial machinery. It’s time to go deep.

Persistence and immutability

There are any number of wonderful presentations about using tree-structured indexes to provide reasonably efficient access to a data stucture and structure sharing to create modified copies cheaply. If you search, you will run across a fair number of presentations that deal with hash array-mapped tries (HAMTs); we will cover HAMTs when get to PersistentHashMap.

Vectors can be managed somewhat more simply. A more focused search term for what we are implementing would be persistent bit-partitioned vector trie. Of the material I found, definitely the most relevant is a series of five posts by Jean Niklas L’orange:

- Understanding Clojure’s Persistent Vectors, pt. 1

- Understanding Clojure’s Persistent Vectors, pt. 2

- Understanding Clojure’s Persistent Vectors, pt. 3

- Understanding Clojure’s Transients

- Persistent Vector Performance Summarised

The posts are directly about the data structure we are implementing. I see no need to duplicate what is done quite well in his presentation. Go read the articles. I will, however, present a few key notions so we can get to the code quickly.

The vectors we are implementing are compact. The elements of a vector of size n are indexed 0 to n-1. There are no holes. This makes vectors simpler than HAMTs.

We cannot simply use an array as the basis for a vector. Immutability and persistence together make this too inefficient. If you had a 1000-element vector and changed the value in one position, you’d have to create a second 1000-element vector – you can’t change the value in the array you have. We’re going to need to break our vector up into pieces.

The most extreme way to break it up is into individual elements. We could provide access via a binary tree, where the bits of the index tell us successively whether to go left or right, and the values are held down in the leaves of the tree. This is not hard to implement but extremely inefficient. The number of accesses needed to get to an element is proportional to log-base-2 of the vector size – For even modestly-sized vectors, this is too much. And the tree nodes are scattered all over memory, not a happy thing for modern computer architectures.

If you’ve decided to use tree access in this way, one needs to balance depth, locality, and the amount of copying required for an operation. Experience has shown that a multi-way branching structure can provide this.

Read the articles mentioned above for more details.

In this implementation the branching factor is 32. (Because of some of the bit-twiddling techniques that can be used for efficient calculations, a branching factor that is a power of 2 is preferred.) We will end up with vectors of size 32 or smaller everywhere.

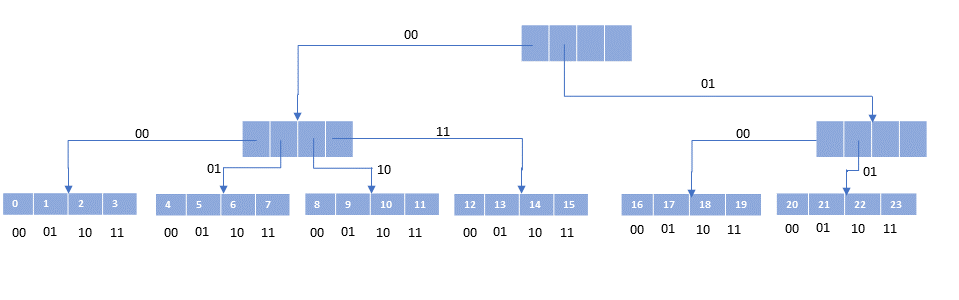

Because we do not have to deal with holes, everything can be packed tightly. This means at every level of the tree, the nodes are packed as far left as possible. Also, we design the tree so that the leaf nodes, where the actual data is kept, are all at the same level. And each leaf node will have 32 data elements in it. This gives a picture like the following. (To make the pictures readable, I will use a branching of 4 instead of 32.)

(The numbers appearing in the leaf nodes are their indexes.)

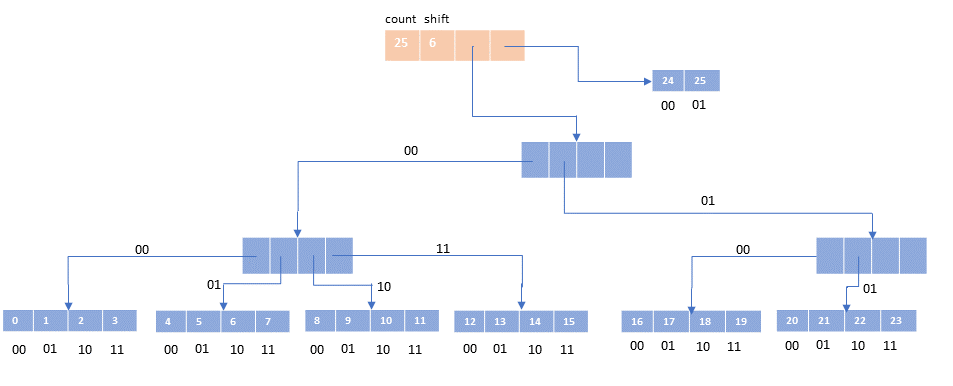

Given what I just said about leaf nodes being full, the leaf nodes will have number of elements that is multiple of four (or 32 in real life). What if your vector has 26 elements? The ‘extra’ two elements are stored in the tail, a short vector of size at most the branching factor to hold the overflow elements.

The vector itself is an object that holds the count of elements, and indication of the tree depth, a pointer to the root of the tree, and a pointer to the tail.

Note that we can find an element given its index fairly easily. The first step is to determine whether the desired element is in the tail. If so, you can just take the last two bits of its index and use that to access the tail array. 25 = binary(011001), the last two bits are 01, so access tail[1].For an index not in the tail, we use pairs of bits to indicate our path down the tree.

19 = binary(010011) = 01 + 00 + 11 = 1 / 0 / 3. Follow that path in the picture above to get to element #19.

We have enough pictures to get started.

Let’s code!

We need a node class.

[<AllowNullLiteral>]

type PVNode(edit: AtomicBoolean, array: obj array) =

member _.Edit = edit

member _.Array = array

new(edit) = PVNode(edit, (Array.zeroCreate 32))

Please, please, ignore that edit field. It won’t be needed until we deal with transience. For now it’s just going to get copied around. Each node has an array in it. For an internal node, the array will hold the nodes at the next level. For a leaf node, the array holds the actual values in the vector.

The vector itself is a header containing some bookkeeping and pointers to the root node and the tail.

type PersistentVector(meta: IPersistentMap, cnt: int, shift: int, root: PVNode, tail: obj array) =

inherit APersistentVector()

new(cnt, shift, root, tail) = PersistentVector(null, cnt, shift, root, tail)

Ignore APersistentVector for now. It is analagous to ASeq, an abstract base class providing some common code (shared by PersistentVector, AMapEntry, and MapEntry). Very straightforward. I’ll write a little about it later on. You also can ignore the meta: IPersistentMap – PersistentVector supports metadata. (Another post for another day.)

cnt is the count of items in the vector. root and tail are as mentioned. shift indicates how deep the tree is. That could be computed from the count, but it is convenient to have it computed and at hand. And it is not the depth itself, but rather indicates the amount we have to shift the index in our bit-twiddling operations to compute access paths.

In the example above, with four-way branching, we needed two bits to determine the next entry to look at. The depth of the tree is 3. The first shift we need is 4 which is (tree_depth - 1) * 2. As we move down the tree, we need to shift two less each time. At the bottom, the needed shift is 0 and we can just mask off the last two bits directly.

In our actual code, using 32-way branching, the shift at the root is (tree_depth -1)*5;

that number is the one stored in the shift field in the vector object.

You’ll see us passing the shift amount down to recursive calls. Whenever you shift-5, that’s what’s going on. You will see shift+5 exactly once - when a cons operation forces us to make the tree one level deeper.

Indexing

With this in mind, we can code up nth, the indexing accessor. First, we have to decide if we are looking in the tree or in the tail. If the branching factor is 32, we need to know the closest multiple of 32 less than our count. I can think of three ways to compute this:

// modulus

let im1 = i - 1

im1 - (im1 % 32)

// divide/multiply

(( i - 1) / 32) * 32

// act all shifty

((i-1) >>> 5) <<< 5

The - 1 is there to handle exactly multiples of 32 properly. (Work it out.) The ‘shifty’ version is the ‘divide/multiply’ version translated into shift operations: Shift to the right to clear the bottom bits out (that is equivalent to dividing by 32), then shift left (equivalent to multiplying by 32). Whichto use? Shifting. It is generally accepted that shift operations are faster than div/mod operations (though some compilers are smart enough to deal with it). I benchmarked it just to convince you (and me). See the endnote. Thus we code

member _.tailoff() =

if cnt < 32 then 0 else ((cnt - 1) >>> 5) <<< 5

Read this as “the offset of the tail is N items”.

If we are looking up an index i <= this.tailoff(), we are in the tree, not the tail. If we are in the tail, we just need the last five bits to of the index to provide the index into the tail array.

At each level we shift right to get to the bits we are interested in and then mask them off. Essentially:

node.Array[(i >>> shift) &&& 0x1f]

The following procedure will return the object array in the PVNode or the tail (also an object array).

It uses tail recursion to work its way down to the leaf level. The shift quantity decreases by 5 at each level until there is no need to shift – that is the leaf level.

member this.arrayFor(i) =

if 0 <= i && i < cnt then

if i >= this.tailoff () then

tail // this tail is the one in the PersistentVector itself

else

let rec loop (node: PVNode) shift =

if level <= 0 then

node.Array

else

let nextNode = node.Array[(i >>> shift) &&& 0x1f] :?> PVNode

loop nextNode (shift - 5)

loop root shift // this shift is the one in the PersistentVector itself

else

raise <| ArgumentOutOfRangeException("i")

Given the array where the index is located, the last five bits of the desired index tell you where to go in the array. Thus:

interface Indexed with

override this.nth(i) =

let node = this.arrayFor (i)

node[i &&& 0x1f]

override this.nth(i, nf) =

if 0 <= i && i < cnt then (this :> Indexed).nth (i) else nf

That’s it. That’s the entire code to access an element by its index.

Note the for the one-parameter version, if you pass an index out of the range [0,cnt-1], the arrayFor call will throw an exception. The two-parameter version checks for being out of bounds and returns the supplied ‘not found’ value instead.

Adding an element

There are three important ‘modification’ methods. The only way to add an item is via cons. The interface IPersistentVector has its own version that is convenient because it returns an IPersistentVector, thus allowing chaining of calls. Adding occurs at the high end only. IPersistentVector.assocN allows the change of value at an index. IPersistentStack.pop removes the ‘topmost’ element. Thus, adding and removing are at one end only.

Of course, these operations don’t modify anything. They all return a new PersistentVector with the desired content. This requires copying of intermediate nodes. We’ll cover cons. pop just does the reverse. assocN feels like a bit of both.

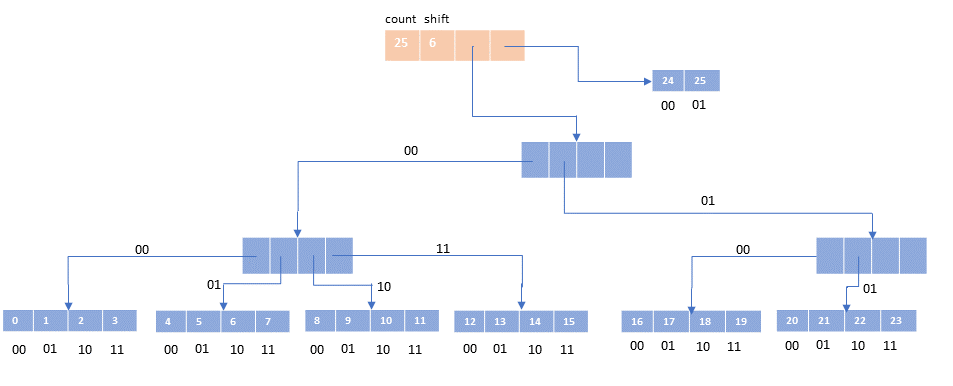

Take another look at the picture from earlier:

and imagine adding elements iteratively. There are three situations we will encounter.

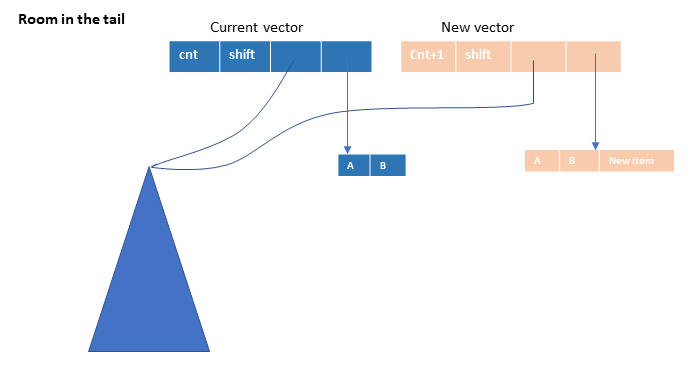

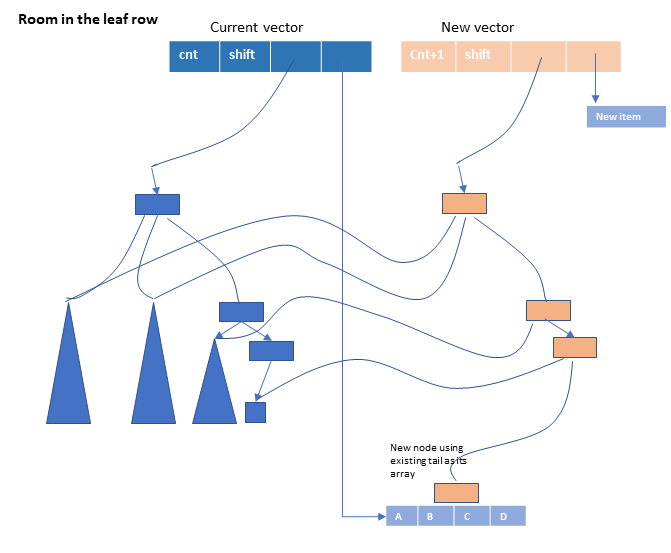

- In the picture above, there is room in the tail. We can create a new tail vector, and a new

PersistentVectornode with an incremented count, the samerootand the new tail. We can keep doing this until we have a full tail. (It is okay for the tail to be full.)

- The tail is full, but there is room in the leaf row to add another leaf. We’ll have to figure out how to detect this, but essentially we create a new node using the current tail as its array, recreate the path up to the root, with copies to any nodes not on that path, and put the new element into a new tail array.

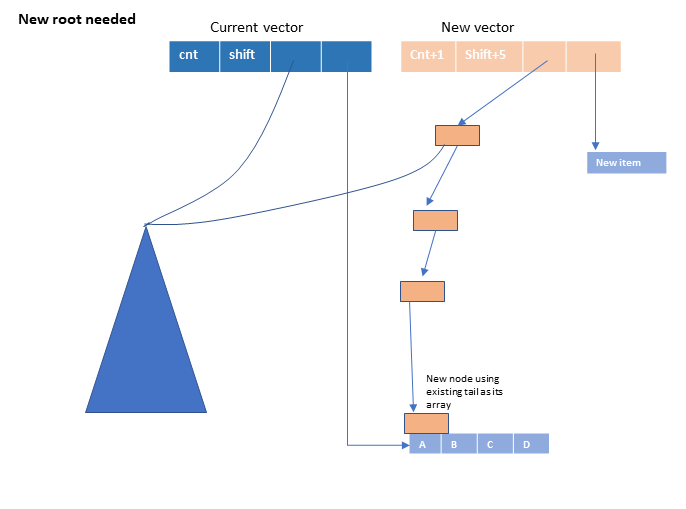

- There is no room in the leaf row. We have to increase the depth of our tree by creating a new root node. The existing tree becomes the leftmost child of the new root, and we establish a set of nodes leading down to the new leaf node.

Our code for cons directly reflects these three cases:

interface IPersistentVector with

override this.cons(o) =

if cnt - this.tailoff () < 32 then

// room in the tail

let newTail = Array.zeroCreate (tail.Length + 1)

Array.Copy(tail, newTail, tail.Length)

newTail[tail.Length] <- o

PersistentVector(meta, cnt + 1, shift, root, newTail)

else

// tail is full, push into tree

let tailNode = PVNode(root.Edit, tail)

let newroot, newshift =

// overflow root?

if (cnt >>> 5) > (1 <<< shift) then

let newroot = PVNode(root.Edit)

newroot.Array[0] <- root

newroot.Array[1] <- PersistentVector.newPath (root.Edit, shift, tailNode)

newroot, shift + 5

else

this.pushTail (shift, root, tailNode), shift

PersistentVector(meta, cnt + 1, newshift, newroot, [| o |])

The first test is for room in the tail. We create a new tail and new PersistentVector with that tail. The count is one greater, the shift and root are the same.

If the tail is full, we will need a new PVNode to put in the tree. Its array can be the current tail. (No need to copy – everything is treated immutably.) We then have to deter

mine if the root needs to split. The magic incantation (cnt >>> 5) > (1 <<< shift) does the trick.

That expression stopped me cold when I first saw it. I decided to just type it in and keep on coding. Under the general theme of “no line of code unexamined”, I knew I’d have to come back to it. Here goes.

I’ll actually solve it generally. Let

bbe our branching factor;bwill always be a power of 2, sayb=2^k. In our pictures above,b=2andk=2; in our code,b=32andk=5. Letdbe the depth of the tree. Recall from above thatshift=(d-1)*k.What is the capacity of a tree of depth

d? At levelj(j=1at the root), there are2^(j-1)nodes. Hence at the leaf level there will beb^(d-1)nodes. Each node holdsb = 2^kentries, so the total capacity when the tree has depthdisb * b^(d-1).There is not enough room in the leaves if

cnt > capacity, which is to saycnt > b * b^(d-1). Equivalently,cnt/b > b^(d-1). Substituting2^kforb, we havecnt/(2^k) > (2^k)^(d-1) = 2^(k*(d-1)) = 2^(shift)Dividing by a power of two can be done by shifting right by the exponent. A power of two can be generated by left shifting

1by the exponent. And we arrive at the condition(cnt >>> k) > (1 <<< shift)in our case, with

k=5.

Now (perhaps) I can sleep at night again.

The work to establish the new nodes required for immutability is done by pushTail for the ‘room-in-the-leaves’ case and newPath for the root-splitting case. It turns out we also need newPath in pushTail.

(If you look in the pictures above, there is a simiar new path created in the two pictures.)

Confession: whenever I look at recursive algorithms for tree hacking, I feel a sense of wonderment. It’s like magic ( = “sufficiently advanced technology”). Yes, I’ll dig in and figure it out. But then I like to go back and just appreciate it as magic. It’s good to have a sense of wonder in our lives.

Which is to warn you that you’re going to have to find your own way to realization on the following two pieces of code. I’ll help a little. Then you’ll have to draw your own pictures, or whatever works for you.

Consider pushTail.

member this.pushTail(shift, parent: PVNode, tailNode: PVNode) : PVNode =

let subidx = ((cnt - 1) >>> shift) &&& 0x1f

let nodeToInsert =

if shift = 5 then

tailNode

else

match parent.Array[subidx] with

| :? PVNode as child -> this.pushTail (shift - 5, child, tailNode)

| _ -> PersistentVector.newPath (root.Edit, shift - 5, tailNode)

let ret = PVNode(parent.Edit, Array.copy (parent.Array))

ret.Array[subidx] <- nodeToInsert

ret

It’s a recurvise algorithm. In essence we descend to the leaf and create nodes and hook them together as we come back out. At any level we are going to be adding a new node into our array of nodes – well, actually, because of immutability, we will be creating a copy of ourself with the new node added. The subidx is the index where that new node will go. You can see in the PVNode(parent.Edit, Array.copy (parent.Array)) where we create a copy of ourself; the next line inserts the new node into the copy. What is the new node? That is the code for nodeToInsert.

What is the new node to insert? If we are the bottom (shift=5), then it is tailNode – we’ve been passing that down from the very top call. It is a node created from the tail of the vector, the one that is full but not yet in the tree.

If we not at the bottom, we look at what is in the place where the new node should go.

If there is a node there, then we recursively call pushTail to push the tail node down there. But if the place where the new node should go is currently unoccupied (fallt hrough to the _ default), what should we do?

We need to create a left-leaning path down to the correct level – all new nodes. (Take a look at the root-split picture above. Same thing happening, just further down in the tree.) That is the job of newPath.

And newPath is mercifully short and perhaps easier to master.

static member newPath(edit, level, node) =

if level = 0 then

node

else

let ret = PVNode(edit)

ret.Array[0] <- PersistentVector.newPath (edit, level - 5, node)

ret

We just build a path of nodes in the 0 index at each level down to the bottom. Expressed recursively.

If you’ve made it this far, the rest of the PersistentVector code is mostly fairly straightforward mechanics. (With the caveat that pop and assocN are at a similar level of complexity with cons – but not anything substantially new.)

Except for transience. That’s next.

After that, perhaps, transcendence.